Our New Legacy: Residential School Survival at Whitecap Dakota First Nation

Too often, the stories told about residential schools end at the trauma inflicted on First Nation communities, and do not tell of the work that communities doing to confront and heal from this legacy.

At Whitecap, we are all inheritors of the residential school legacy. Whether you are a survivor of residential schools, a descendent of a survivor, or are a member of an Indigenous community, the effects of residential schools remain on our culture, language, & families.

Traditionally, Dakota children were educated within their extended families. Over the one hundred or so years that residential schools were operating on the prairies, Whitecap children were separated from their families and sent far from home to schools in Regina, Duck Lake, Prince Albert, Red Deer, Alberta and Brandon, Manitoba. The earliest Whitecap students who attended residential schools are amongst those pictured here. Some never made it home. Others contracted deadly illnesses and were sent back to their families.

Students in front of the day school at Whitecap Dakota First Nation, circa 1892. Back row (left to right): Charlie Eagle, Jackie Baker, Lucy Littlecrow, Dan Eagle, Mary Whitecap. Middle row (left to right): Wabidoo Hawk, Joseph Chuncu, Beckie Whitecap, Joe Hawk, Sam Buffalo, Emma Littlecrow, Lizzie Hawk. Front row (left to right): Jim Whitecap, David Hawk, Nellie Whitecap, Eddie Whitecap, John Poordog.

As many have pointed out, although they were called “schools,” these institutions did not have teaching as their core objective. Children worked most of the day, often in horrendous conditions, near starvation, poorly clothed, and suffered abuse.

This neglect did not go unrecognized at Whitecap. Parents, First Nations leaders, teachers and others called for reform or an end to the “schools.” But the Canadian government ignored these calls.

In 1904, a local teacher at Whitecap, Mrs. Tucker, protested the harms of the residential school system on Whitecap children in a letter written to the Department of Indian Affairs. In the letter, she indicates that 5 out of 8 children who had been sent to residential schools had died.

These children’s names can be seen in the picture below, and include:

Beckie Whitecap

Joseph Road (Chancu)

Sam Buffalo

Aggie Birch

Eddie Whitecap, along with his brother and two sisters.

Library and Archives Canada (LAC), RG10 Volume 6327 File 660-1 pt 1, 1-2.

Library and Archives Canada (LAC), RG10 Volume 6327 File 660-1 pt 1, 1-2.

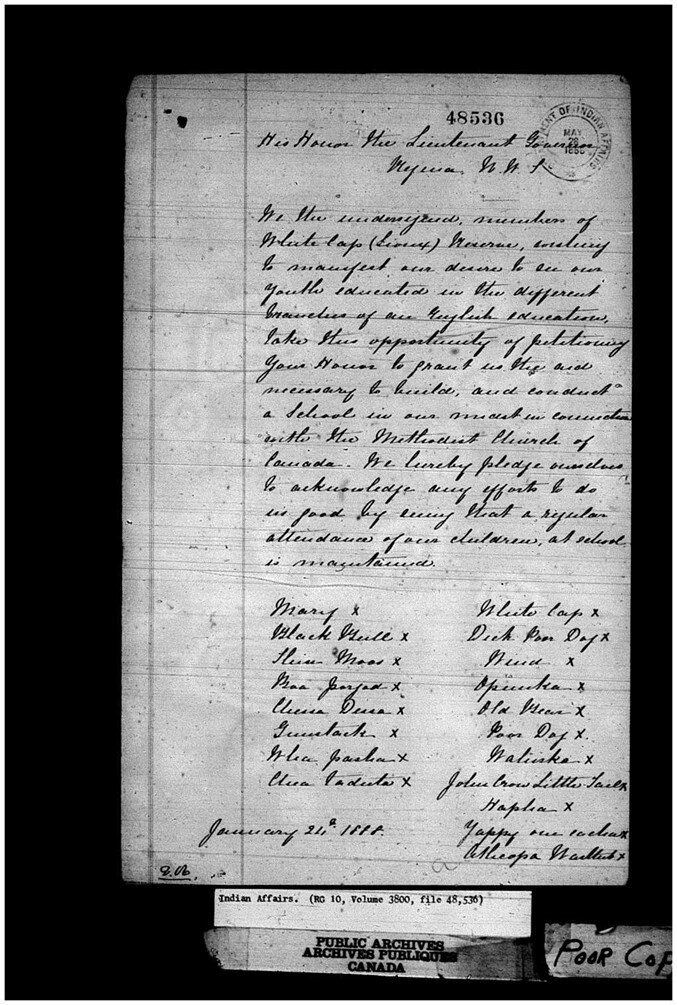

The Whitecap community tried to keep their children at home and petitioned the federal government for a Day School on-reserve in 1886 (LAC, RG10 Volume 3800 File 48336).

LAC, RG10 Volume 3800 File 48336.

However, the school was still run under the paternalistic eye of the Department of Indian Affairs. This, along with mounting colonial pressures over the years, meant that many children were forced to leave their families to attend residential schools. Further research needs to be conducted on how many of these children did not make it home—either because of illness and death, or because they felt they no longer belonged in the community.

Today, over fifty living survivors of residential schools reside at Whitecap Dakota First Nation.

Over the past few decades, Whitecap has gone to great lengths to resume control over education, culture, and language. The construction of a new school in 1996, the establishment of a co-governance alliance with Saskatoon Public Schools, and the infusion of language and culture at every level of education are just a few of the efforts made to regain self-determination over education. Whitecap Elders, leaders, and community members have spent countless hours developing programs and services to bring back the connections, language, and culture that was taken away through residential schools. This work is being done together as a community.

This November, Whitecap Dakota First Nation will hold the community vote to determine whether to enter into a Self-Government Agreement, which would provide even more control over culture, language, and education. It would also make the community the first in Saskatchewan to enter into self-government arrangements with the federal government. At the heart of the movement toward self-governance is the effort to regain and retain connections to our community and families and provide them with safe and healthy lives that were not available to so many of the previous generations.

Residential School Survivor and Elder Elmer Eagle said:

We've been under the control of the government. I mean, I grew up in it. I grew up in the whole system. I went through residential school and all the negative stuff that the government put in front of us to keep us down basically. But still we rose above that. And now with this self-government agreement, it's just going to keep us taking further and further in a positive direction. (Elmer Eagle, interview, May 6, 2021)

This road toward self-determination is the legacy of Whitecap that will endure, and it is the story that needs to be told as we commemorate the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

FRANK ROYAL is a Councillor for the Whitecap Dakota Government and has been active in the community’s governance, and conducting research on Dakota history and genealogy, for over two decades.

STEPHANIE DANYLUK works for the Whitecap Dakota First Nation, conducting history and policy research in support of Whitecap’s governance, language, culture, and heritage initiatives.